Thought Leadership

Discovering the Causes of Cleft, Part 2

The International Family Study gathers critical information about the causes of cleft conditions. Former project manager Frederick Brindopke answers frequently asked questions about the study.

At the Operation Smile ongoing surgical program site in Cebu City, former International Family Study (IFS) project manager Frederick Brindopke is busy collecting saliva samples for genetic analysis from each baby waiting for surgery. He holds one of the infants in his arms and carefully swabs the inside of the cheeks. The baby just curiously watches Frederick, fascinated by the tickling feeling.

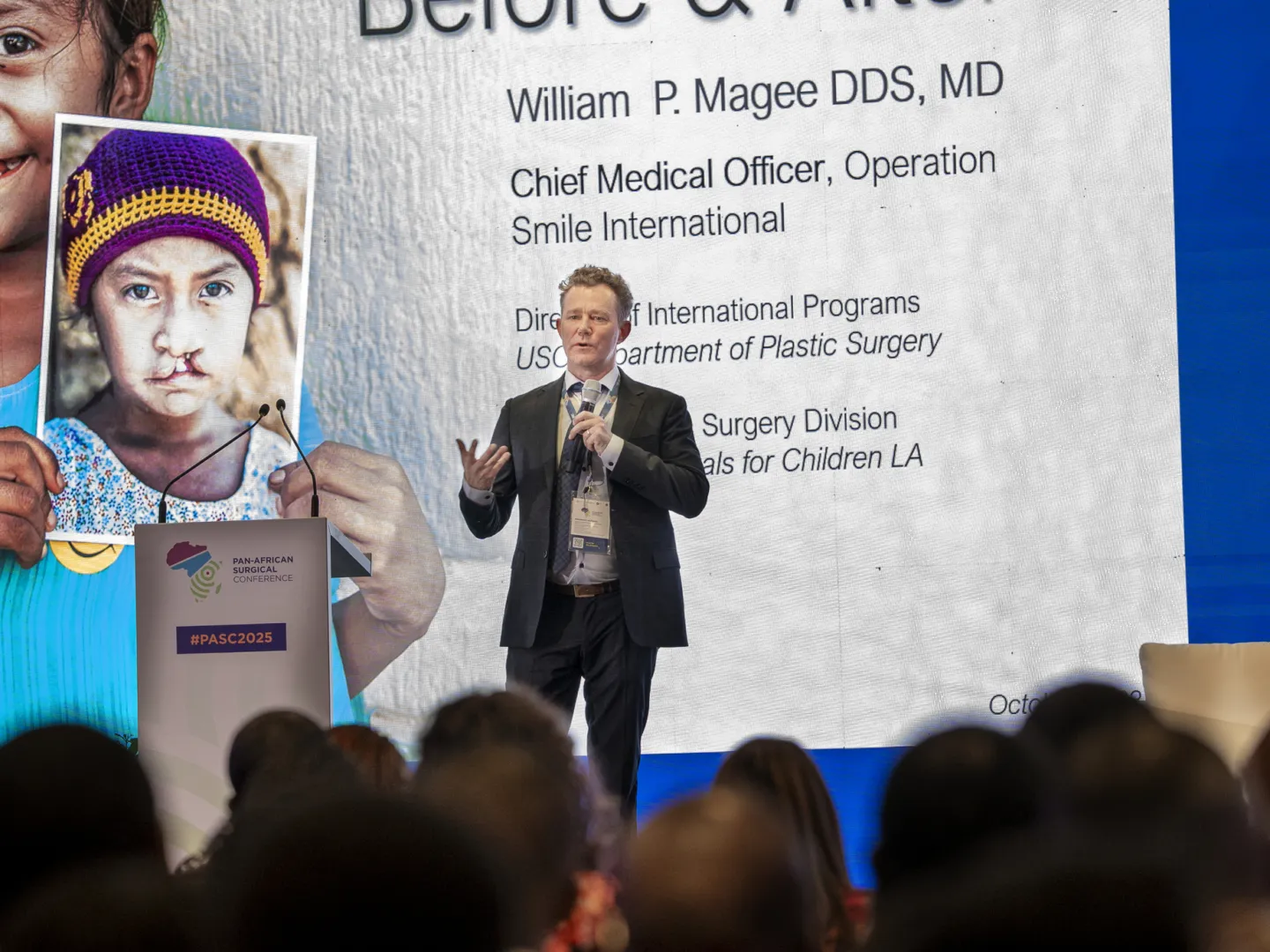

More than 18,000 individuals have experienced this simple, painless collection method during the course of IFS, which is a collaboration between Operation Smile, University of Southern California and Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles aimed at finding potential risk factors of cleft conditions. The first study of its kind, IFS blends the data from this genetic analysis with findings from questionnaires on environmental exposures and lifestyle habits to provide the most comprehensive understanding of the causes of cleft in low- and middle-income countries. The ultimate goal of the study is to put this evidence into action to prevent cleft conditions before they develop and to better understand the mechanisms of cleft and what can increase risk in low- and middle-income areas.

Amid his busy on-site schedule, we asked Brindopke for deeper insight into this study.

Q: How common are cleft conditions?

A: “It really varies. It is important to notice that research so far has been lumping cleft lip and palate together, but more and more we find there’s different incidences for them. But just cleft lip and cleft palate grouped together is very different throughout the world. The highest rates are seen in Southeast Asia, about one in 500 or two in 1,000, so it’s among the highest in the world. Whereas in Africa, we see different rates of cleft of about one in every 1,000 children born.

Q: What about cleft cases in the U.S. or Europe?

A: “It’s about on par, a little bit more common than Africa. The thing is we don’t see it as much because they’re treated very quickly since surgical access is much more available in the U.S., so, on average throughout the world, we say one in 700.

Q: Describe IFS and what makes it such a unique study?

A: “The study is really a unique partnership between a nonprofit that’s providing medical care, as well as academic partners and holistic and comprehensive care partners such as the Children’s Hospital (Los Angeles). We’re also a unique study in that we have some of the largest collections of genetic information regarding clefts in the world as of now.

“We are trying to look at risk factors that increase the chances of developing clefts and trying to see what environmental exposures these parents and their families are being exposed to.”

Q: Why are families like Loraine’s so valuable to IFS research?

A: “These kinds of families can definitely give us information, specifically in the genetics. There are specific genes that are being passed along. And we can also look at if they have protective genes — why certain members of their families didn’t develop clefts while others did. But you also need to take into consideration if there is an environmental exposure that is affecting everyone as well. We hope to find what is causing the problem in this family, and it could potentially be a new cause of cleft that has not been reported before.”

Q: Why is understanding data collected from the fathers of children with cleft conditions critical to the study?

A: “Including the fathers in the study also makes our research different from others, because in a lot of scientific journals and scientific studies, the father hasn’t been included. Part of that is logistics, because fathers are hard to collect. Typically, the mother is in charge of their child’s health, taking the child to the doctor and so on. But fathers really represent half of the child’s genes, so we think that is a vital key in understanding cleft lip and cleft palate, as well as the risk factors.”

Q: How does the research help the patients and families it studies?

A: “What we hope to give back to these communities is overall knowledge. Understanding the risks for developing clefts, understanding what kind of behaviors lead to higher likelihood of cleft lip and cleft palate developing. So really, we think that information is valuable but we also think we need to do it in terms of preventative measures and implementations in the community — whether that’s anti-smoking campaigns or campaigns to enhance prenatal care for mothers — so that they’re being seen as soon as they’re pregnant to receive the vitamins and nutrition they need.

“Unfortunately, it’s too late for the children who come to the [programs] — they’ve already been born with the cleft lip or cleft palate. But what we’re trying to say to these families is that, ‘Your child is going to grow up and have kids of their own one day, so hopefully we have better answers for you in terms of health behaviors you can try to avoid, and certain things that will elevate your children’s risk for cleft lip and cleft palate,’ and with that knowledge, hopefully empower communities to try to reduce the burden globally of cleft lip and cleft palate throughout the world.”